England, 1981. In some rural South West discos menace was in the air; no night complete without a fight, Skinheads attacking whoever riled them, flick knives at the ready. Tracks by Madness, The Beat and The Selecter were the soundtrack to these nights. These bands played ska music, a popular Jamaican genre from which reggae evolved.

But when “Ghost Town” by The Specials came on, everyone stopped.

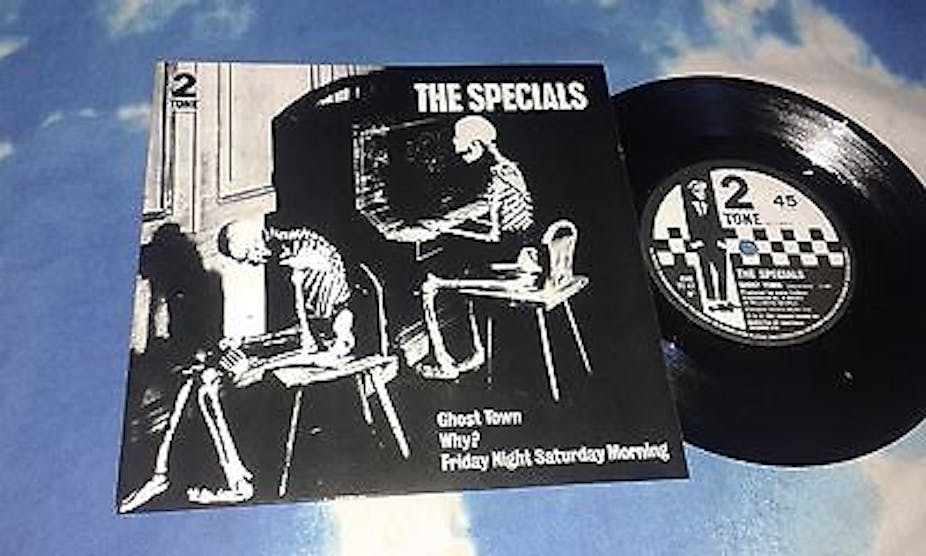

Formed in 1977 and arguably the most influential band of the UK’s 2 Tone Ska scene, “Ghost Town”, a skewed ska oddity, was written by Jerry Dammers, The Specials’ keyboardist and released in June 1981. It was their last song before splitting up and reforming as The Special AKA and stayed at the top of the UK charts for three weeks.

Odd, eerie song

It’s an odd, eerie song, nodding to pop convention and sitting wilfully outside of it. It’s included, in passing, in Dorian Lynskey’s beautifully written book on protest songs, “33 Revolutions Per Minute”, but unlike the band’s “Free Nelson Mandela” does not merit its own chapter.

Perhaps because “Ghost Town” cannot be “placed”. It’s not explicitly against any one event. It does not exhort its listeners into any one particular political view. It is not part of any one social movement for change. It is, rather, a stealth protest song.

Starting with a Hammond organ’s six ascending notes before a mournful flute solo, it paints a bleak aural and lyrical landscape. Written in E♭, more attuned to “mood music”, with nods to cinematic soundtracks and music hall tradition, it reflects and engenders anxiety.

The whispered chorus of “This Town/ is coming like a Ghost town” is then heard, followed by front man Terry Hall’s deadpan vocals lamenting how “all the clubs have been closed down” because there is “too much fighting on the dance floor”.

One of the clubs referred to in the song was The Locarno in Coventry, the Midlands UK city where the 2 Tone record label started in the late 1970s.

2 Tone had emerged stylistically from the Mod and Punk subcultures and its musical roots and the people in it, audiences and bands, were both black and white. Ska and the related Jamaican Rocksteady were its musical foundations, sharpened further by punk attitude and anger. It was this anger that Dammers articulated in “Ghost Town”, galvanised both what he had seen on tour around the UK in 1981 and what was happening in the band, which was riven by internal tensions.

England was hit by recession and away from rural Skinhead nights, riots were breaking out across its urban areas. Deprived, forgotten, run down and angry, these were places where young people, black and white, erupted. In these neglected parts of London, Birmingham, Leeds and Liverpool the young, the unemployed, and the disaffected fought pitch battles with the police.

“Ghost Town” was the mournful sound of these riots, a poetic protest. It articulates anger at a state structure, an economic system and an entrenched animosity towards the young, black, white and poor. It asks,

why must the youth fight against themselves.

In his book Lynskey argues that “like all great records about social collapse, it seems to both fear and relish calamity” and its ambiguity allows it to soundtrack more than the riots about which it was written. It is an angry elegy for lost opportunity, lost youth, an acid flavoured lament for what was and what could be.

The streets that The Specials conjure up in “Ghost Town” are inhabited by ghosts; dancing is a memory, silence reigns. The sounds of life, community, creativity are no longer, “bands don’t play no more”. In the song’s short bridge section in the bright key of G♭ major, Hall asks us to,

remember the good old days/before the ghost town/ when we danced and sang/ and the music played ina de boom town".

And as Charles Dickens wrote in his “A Christmas Carol”, ghosts are spectres not only of the past, but of the present and future too, traces of what was, is and might have been. “Ghost Town” is the haunting track of thousands of lost futures. And in 2011, when England erupted again and the cities burnt, “Ghost Town” was remembered and replayed.

Strange music video

Its audio-visual manifestation was also strange. The music video was directed by Barney Bubbles and filmed in the East End of London, Blackwell Tunnel and a before-hours City of London. Opening with upshots of brutalist grey tower blocks to the sound of those Hammond organ chords and flute, it seems as though there is no one in town but The Specials, who are all crowded into a 1962 Vauxhall Cresta, careering through the empty streets and lip syncing.

This in itself constitutes “eerie” if we use cultural critic Mark Fisher’s work, “The Weird And The Eerie”, to understand it. He wrote how,

The sensation of the eerie occurs either when there is something present where there should be nothing, or there is nothing present when there should be something.

Here, in a major capital city, where the streets should be teeming, there is no-one but The Specials, a group of young black and white men, from a depressed and demoralised Midlands town. They are in charge.

As if to further underline this, the camera was placed on the car bonnet so we see The Specials as if they are crashing into us. And when they all sing “yah, ya ya, ya, yaah, ya, ya, ya, ya, ya, ya…”, they seem like an insane Greek chorus, before Lynval Golding, the band’s rhythm guitarist and vocalist, murmurs the last line “the people getting angry”. The song fades out in dub reggae tradition, inconclusive, echoing.

Not a dance track

So what did those fight-ready Skinheads do in those small town discos when “Ghost Town” came on? Not moonstomping, not smooching. This was not a dance track. It wasn’t the “romantic” one the DJ played at the end of the night.

When “Ghost Town” played, the Skinheads sang along with Terry Hall, smiled manically and screeched. They joined into to the “ghastly chorus” and became, for a few minutes, part of that army of spectres. Because protest sometimes has no words.

It’s just a cry out against injustice, against closed off opportunities by those who have pulled the ladder up and robbed the young, the poor, the white and black of their songs and their dancing, their futures. Drive round an empty city at dawn. Look at the empty flats.

See the streets before the bankers get there and after the cleaning ladies have gone. And put young, poor, disadvantaged people in that car. See how “Ghost Town” makes sense. Now.

Protest music has made a serious comeback over the past five years. This article is the first in a series featuring Songs of Protest from across the world, genres and generations.